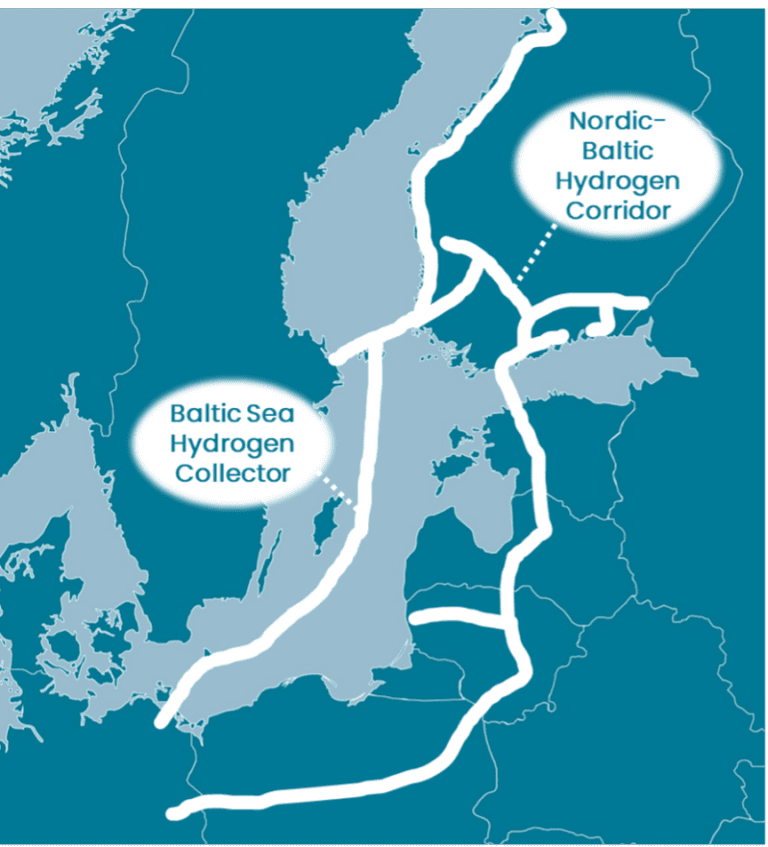

In early January, gas system operators from Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Germany signed an agreement to explore the feasibility of the Nordic-Baltic Hydrogen Corridor, which is expected to be completed by mid-2024. The aim is to examine the possibilities of establishing a cross-border hydrogen infrastructure connecting Northern European green hydrogen production with Central European consumption.

Planned hydrogen infrastructure opens up new opportunities

The planned hydrogen infrastructure would enable large-scale green energy transmission over long distances, facilitating numerous opportunities. The development of a hydrogen pipeline through Estonia means that we can produce green energy regardless of the capacity of existing electricity connections, ensuring a more stable price for our producers. Additionally, it would enhance our energy security and create opportunities to use cheap green energy for hydrogen production when the electricity supply exceeds demand. More affordable electricity and hydrogen create opportunities to develop energy-intensive industries and support the Estonian economy. However, to create a market, efficient infrastructure is needed. In the case of hydrogen, this means a pipeline connecting potential production and consumption in Estonia with the rest of Europe.

The Nordic-Baltic Hydrogen Corridor is a significant EU project

The list of European Commission joint interest projects published in November included many hydrogen infrastructure projects, including the Nordic-Baltic Hydrogen Corridor. While designation as a joint interest project does not guarantee financial support or confirmation of further development, it helps to streamline regulatory and permitting processes, as well as apply for EU funding. Additionally, among the joint interest projects is the Baltic Sea Hydrogen Collector, connecting Finland and Sweden with Germany. Given Estonia’s potential to produce renewable energy onshore and offshore in much larger volumes than we currently consume, this would provide the opportunity to produce large volumes of green hydrogen, connecting production with consumption and storage sites. Taking one example of a potential offshore wind farm near our western coast, the green hydrogen produced there could be consumed by industry in Estonia ten years from now, stored long-term, or sold to existing heavy industry in Lithuania, Poland.

Planned Baltic Sea hydrogen corridor “D” (European Hydrogen Backbone, 2023) [The information on the map is drawn based on the European Hydrogen Backbone – Implementation roadmap – Cross-border projects and costs updates (November 2023, p.17)]

In the Baltic Sea region, the launch of the hydrogen economy is also being developed by the BalticSeaH2 project, the goal of which is to create a large-scale cross-border hydrogen valley between southern Finland and Estonia. The project co-financed by the EU has a total of 40 partners from nine countries, including the Estonian Hydrogen Cluster.

A cheaper way to transport energy

Although detailed infrastructure cost estimates are still emerging, the planned hydrogen infrastructure will likely be a significantly cheaper way to transmit energy than the same volumes required by electricity cables and transmission lines. Connecting with the rest of Europe develops the energy market, offers market participants more options for buying/selling energy, and enhances energy security, allowing Estonia and Europe to reduce dependence on energy imports. Hydrogen infrastructure promotes green energy production, ensuring the ability to store surplus energy long-term and offering the opportunity to produce green hydrogen from electricity at a low cost. This, in turn, helps improve security of supply by providing a solution to cover peak demand when alternatives are lacking and enables the conversion of gas-fired power plants to hydrogen without wind and sun.

Hydrogen infrastructure would bring Estonian electricity prices closer to those of Scandinavia

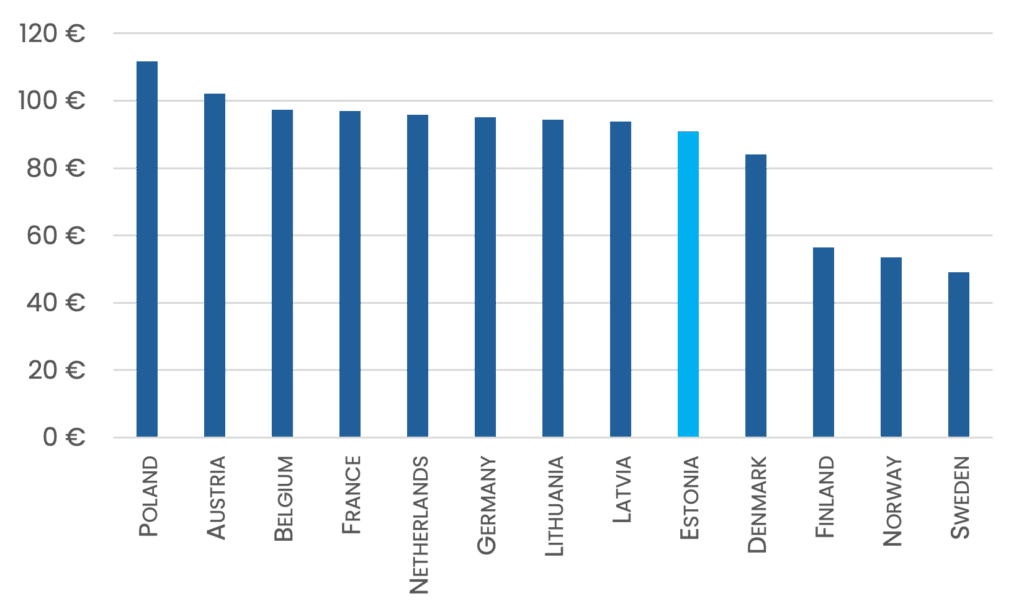

The planned hydrogen infrastructure would bring cheaper electricity prices to Estonia, helping to narrow the gap with Scandinavian prices, with lower electricity prices providing opportunities to develop industry competitively. High electricity prices have been widely discussed in previous years, but when comparing Estonia with other Central and Northern European countries, lower wholesale prices were only available in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden last year. Cheaper, greener, and more accessible electricity and green hydrogen in Estonia would enable the development of new industries, such as chemical and heavy industries, creating added value and economic growth. These development opportunities would become abundant throughout the hydrogen corridor, significantly supporting the economies of the Baltic countries and the Nordics.

2023 average electricity exchange price EUR/MWh (Nordpool, 2024)[The information on the diagram is from Nordpool “Day-Ahead Prices” 2023 average – for Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, their respective region’s average numbers are available]

Cost reduction requires well-planned support

Analysing examples from the wind or solar energy sectors shows how planned and well-structured support schemes help a growing sector develop economically. At the beginning of the century, it was not economically feasible to build wind farms; it would have been easier and cheaper to continue with fossil fuels. However, recognising the potential and need for green energy, several support schemes were created in Europe, gradually making onshore wind development prices cheaper than fossil energy, and the same can be said for solar energy. Before the energy crisis that began in 2021, the same could have also been said for offshore wind, but higher capital costs and interest rates have made financing such large projects significantly more difficult. Although much emphasis has been placed on the high costs of building offshore wind farms lately, the exact same issue would apply for new fossil plants. Hydrogen production is not at all new, but large-scale green hydrogen production, consumption, and infrastructure development are still in the developmental phase and require targeted support, just as solar and wind energy development did. Further economies of scale, supply chain development, and lowering capital costs are factors that will significantly reduce the price of green hydrogen and offer competition to fossil alternatives.

The study of the Nordic-Baltic Hydrogen Corridor is an important part of launching and promoting the hydrogen economy. If the project proceeds, it is expected to be completed in the first half of the 2030s, but it will help producers and consumers plan and develop their activities much earlier.

Written by Steven Sepp, Estonian Hydrogen Cluster